Maybe there are indeed spirits guiding civilizations, inspiring technological advance, intervening in wars. And maybe they’re not always to be listened to.

To my surprise this morning, drinking my coffee while staring out over the mist-shrouded fields outside my window, I found myself thinking about a peculiar book I really didn’t like, by an author I liked even less.

That book was Pastwatch: The Redemption of Christopher Columbus, by the speculative fiction writer, Orson Scott Card. Better known for his book, Ender’s Game, Card was quite a prolific fantasist, while being perhaps less known for his fanatic Mormonism and his particular disgust for homosexuality. Writing in 1990, Card asserted:

Laws against homosexual behavior should remain on the books, not to be indiscriminately enforced against anyone who happens to be caught violating them, but to be used when necessary to send a clear message that those who flagrantly violate society’s regulation of sexual behavior cannot be permitted to remain as acceptable, equal citizens within that society.

I’d known nothing of Card’s religious fundamentalism until reading Pastwatch, and thus found it a very perplexing book. I’d not sought the work out; there was a copy of it lying around in the “anarchist commune” (read: dysfunctional roommate situation) in which I lived for much of my 20s and 30s, and I was always quite hungry for more books to read.

At the time I read it, I was in what we might call the zenith of my anarchist political trajectory, just before many of the ideas I’d found so fascinating to me began to reveal themselves as both unworkable and also personally destructive. Thus, those who’ve read the book can probably understand why I found the book so repulsively propagandistic that I threw it into the recycling bin when I’d finished it.

Thus, it’s quite amusing to me that the book has been in my head since waking this morning, though I also understand why. For weeks, or even months, I’ve been struggling to find a metaphor to explain a very strange process of which I’ve become increasingly convinced, yet don’t really know how to describe. And that’s what fiction is for, anyway, especially speculative fiction. In such works, we can suspend just enough of the everyday rules that govern our current understanding of the world to try out another understanding in an inconsequential way. Such fiction lets us play with other recognitions, but also allows us to put them aside — if we need — once we’ve finished with the work.

The premise of Pastwatch is admittedly brilliant, since Card himself — despite his heavy-handed moralizing in many of his works — is also quite brilliant. In a not-too-distant future, during a period of inevitable environmental and civilizational collapse, a scientist with a historical research organization — “Pastwatch” — that has found a way to directly observe past events makes an accidental discovery. Though believing the past was unalterable, and thus their technology was only capable of observation, the researcher is surprised to find that a Peruvian shaman in the past senses her presence.

The goal of the research organization was to learn precisely where it was that humanity had gone wrong, and what event precisely had triggered their current state of calamity. They become convinced that the turning point was actually a person, Christopher Columbus, and they become particularly obsessed with the moment Columbus has a vision telling him to sail west, rather than east. Observing that moment repeatedly, they notice that Columbus is interacting with figures whom they cannot see. Adjusting their technology slightly, however, they then realize — to their initial disbelief — that someone is actually speaking to him.

It turns out that this is not the first iteration of Pastwatch, nor of the future. In a previous timeline, a world even more catastrophic had unfolded. Instead of colonizing the Americas, European powers had tried to conquer the Muslim world. Failing, and left deeply weakened, Europe was then conquered by a successor empire to the Aztecs, the Tlaxcalan, resulting in blood-soaked ziggurats raised in every European city and the industrialization of human sacrifice. To change that future, the previous Pastwatch researchers had convinced Columbus to sail across the Atlantic, thus weakening the Aztecs and the Tlaxcalan. This prevented one horrible outcome, but then resulted in another.

In the end, the researchers use the same technology to create a third future, one which results both in the end of human sacrifice and also a less destructive industrial revolution, while scattering information throughout history that would explain to any third iteration of Pastwatch what they had done and why.

In crafting the book, Orson Scott Card plays with a belief core to the founding of Mormonism. Its founder, Joseph Smith, claimed to have encountered an angel named Moroni, a figure who was in life a warrior from the lost tribes of Judah but became, in death, the guiding angel of the Americas. According to the Mormon cosmology, it was Moroni who buried and then later revealed to Joseph Smith the golden plates upon which the Book of Mormon was written. Later beliefs expanded Moroni’s role in history: he is said to be one of the angels John of Patmos described in the Book of the Revelation, and is also said to have guided Columbus to the Americas.

Longtime readers will note with me that this is the very first time in my more than ten years of public writing that I’ve ever even mentioned the Mormons. This surprises me as much as having Card’s book in my head this morning.

My long silence on that matter isn’t because I’ve ever considered Mormonism inconsequential. There are at least 16 million Mormons in the world, and they’ve a rather oversized effect both on American politics and also on the matter of genealogical research. On that latter effect, it’s particularly worth noting that the vast majority of online databases (such as Ancestry.com) were started by Mormons, and the Church of Latter Day Saints built and maintains the largest nuclear-safe underground vault of genealogical records in the world.

Their religious obsession with genealogy is particularly fascinating, as ancestral veneration is otherwise completely absent within Protestant Christianity. Instead, Mormons seem to take Catholic and Orthodox practices of praying for the dead to an extreme level, believing that retroactive baptism ensures an ancestor will join the believer in paradise as part of their eternal family.

More curious to me and more relevant to my work, however, are two obscure occult influences from the 16th century that I’ve yet to see anyone else take up. The first is something I discussed briefly in a previous installment of this series, that of a Portuguese rabbi’s belief that ancient Jews had dispersed throughout the world:

Menasseh Ben Israel is probably best known as Baruch Spinoza’s teacher. He was also a fanatic believer that the indigenous peoples of the Americas were likely the “lost tribes of Judah,” an idea picked up again by Joseph Smith, the founder of Mormonism.

The mythic belief about the lost tribes is tied to the medieval belief in Prester John, a Solomonic figure said to be a Christian king and priest of either India, Ethiopia, or some unidentified exotic land, depending on which version of the story was current. Said to have been a spiritual descendant of Thomas (the “doubting Apostle”) and to rule over a rich Christian kingdom, Prester John became a pastiche of myths, a container for whatever great hope European Christians most needed.

In the 16th century, flushed from the wild tales of gold and strange peoples in the Americas, Spanish and Portuguese Catholics became increasingly obsessed with the belief they’d discovered a mythic kingdom. Early accounts of the vast riches and the complex religious ceremonies of indigenous Americans inspired all manner of wild speculation. Considered in the context of bloody religious strife in Europe, with the Catholic’s power waning and the Calvinist influence increasing, it’s easy to see how the symbol of Prester John — a powerful Christian king whose lands prospered under his leadership — would have held such attraction.

The belief that the conquerors of the Americas had actually discovered the remnants (or outskirts) of Prester John’s kingdom is what then inspired Baruch Spinoza’s teacher, Menasseh Ben Israel, to conclude that the indigenous Americans were lost Jews. This happened because so much of Prester John’s myth was bound up with the mythic elements of Solomon (witness, for example, that a “King David of India” was said to be one of Prester John’s descendants). Also, Solomonic grimoires — magic books purporting to have originated with Solomon or to reproduce the magic he used — were the primary occult texts in circulation among both Jewish and Christian kabbalists at that time. In such a mythic environment, it’s not difficult to see how Ben Israel was convinced about the Jewish origins of indigenous Americans.

I elaborated on the strange relationship between Zionism, Jewish kabbalistic teachings and Calvinism in my previous essay. Calvinist belief in the “elect” and kabbalist teachings about the Jews’ special role in “repairing the world” meshed seamlessly together in Puritan fanaticism and the attempt to build a “New Jerusalem” in North America. These ideas were re-iterated by subsequent generations of Puritan and other Protestant American theologians so frequently that it would have been impossible that Joseph Smith could have not heard of them.

This, then, explains one of the two peculiar occult features of the Mormon cosmology and its founding. That’s the belief that a “lost tribe” of Jews had emigrated to the Americas and then, according to the Book of Mormon, later received the gospel from Jesus during the forty days after his resurrection but before his ascension to heaven. That is, we don’t need to postulate some other explanation for as to how this belief arose within Mormonism, since we can trace its historical origins back to Prester John and Jewish-Calvinist belief in the lost tribes.

Where things get more difficult to explain is the matter of the angel Moroni, and how it was that Joseph Smith used a Solomonic scrying method to find and then translate the Book of Mormon.

It’s well-documented — and now tacitly admitted by the Church of Latter Day Saints — that Joseph Smith worked as a folk diviner and a dowser before claiming to discover the Book of Mormon. Just as well-attested, though less often talked about, is what other kinds of magical practices Smith and his early companions used.

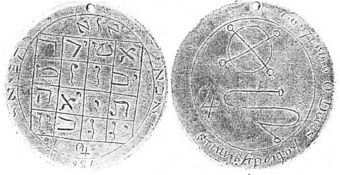

For instance, in one of the official LDS church vaults, there’s a silver disk called the Jupiter Amulet. As described by Reed Durham, Jr., an LDS administrator:

All available evidence suggests that Joseph Smith the Prophet possessed a magical Masonic medallion, or talisman, which he worked during his lifetime and which was evidently on his person when he was martyred. His talisman is in the shape of a silver dollar and is probably made of silver or tin. It is exactly one and nine-sixteenths inches in diameter, and weighs slightly less than one-half ounce.

After months of research, the talisman, presently existing in Utah, (in the Wilford Wood Collection, D. C. M.) was originally purchased from the Emma Smith Bidamon family, fully notarized by that family to be authentic and to have belonged to Joseph Smith, can now be identified as a Jupiter talisman. It carries the sign and image of Jupiter and should more appropriately be referred to as the Table of Jupiter. And in some very real and quite mysterious sense, this particular Table of Jupiter was the most appropriate talisman for Joseph Smith to possess.

“Masonic,” however, is not quite the correct description of the amulet, as it’s a direct copy from the instructions in the 1801 Solomonic grimoire, The Magus:

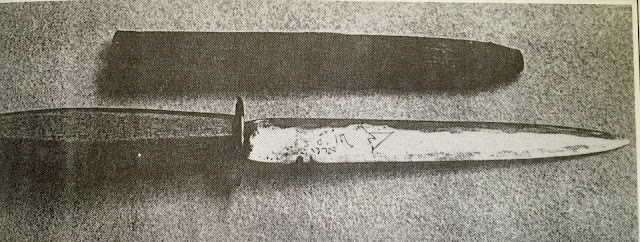

Joseph Smith’s brother, Hyrum Smith, was also in possession of a Solomonic magical knife — described as “Masonic” by Hyrum — known as the Mars Dagger. It bears the glyphs for the spirit (or “intelligence”) of Mars, for Scorpio, and the Hebrew abbreviation for Adonai, all inscriptions recommended by Solomonic grimoires.

Hyrum Smith wasn’t the first owner of the dagger, however; it originally belonged to the father of both the brothers, Joseph Smith, Sr.. Both the elder and the younger Josephs were purported to have drawn magic circles together with the blade.

It’s unclear precisely how either the Mars Dagger or the Jupiter Talisman first came into their possession, but there’s a good argument to be made that it had something to do with a friend of the family (and cousin to the younger Joseph’s later wife), a man named Dr. Luman Walter:

By contemporary reports he was not only a physician, but a magician and mesmerist who had traveled extensively in Europe to obtain “profound learning” – probably including knowledge of alchemy, Paracelcian medicine, and hermetic lore. Other pieces of evidence added to the picture. Three very curious parchments and a dagger owned by Joseph Smith’s brother, Hyrum, have been careful preserved by his descendants as sacred relics, handed down from eldest son to eldest son after his death. Family tradition maintained they were religious objects somehow used by Hyrum and Joseph. When finally allowed scrutiny by individuals outside the family, it was recognized they were the implements of a ceremonial magician. (source)

The aforementioned grimoire, The Magus, was published in 1801, twenty-six years before Joseph Smith, Jr. is said to have encountered the angel named Moroni. Though there’s no evidence of Smith ever being in possession of the book, there’s plenty of reason to suspect his mentor Luman Walter (and even possibly the elder Joseph) had read it. It may have been Walter who created — or at least guided the creation of — the Jupiter Talisman and the Mars Dagger.

Though much of this might initially seem conspiratorial, it’s important to realise that the LDS church itself does not deny the influence of magic and occult practices by their founders. In fact, much of the research and documentary evidence about these matters has been sponsored by and spearheaded by the Mormons themselves, including in LDS-funded academic journals.

Rather than denying these practices and influences, church leaders instead argue that Smith’s use of occult practices were actually in line with God’s will. Especially regarding the use of “seer stones” to find the plates upon which the Book of Mormon was written, LDS organizations rather directly argue that, while such things can be seen as “occult” acts, they are also continuations of Old Testament practices. In other words, they make a distinction between divination and other practices used in accordance with God’s will, and those used for selfish or diabolic purposes.

On the surface, this appears to be a rather startling position. However, it’s much more in line with how such practices were understood both in Joseph Smith’s time and also throughout the history of Christianity. This is the argument made by quite a few historians of magic and Christianity both, a common theme I’ve encountered repeatedly in my research. It’s only very, very recently that we’ve come to assume that Christianity was opposed to all forms of magic, and this assumption has much more to do with the propaganda of Calvinists against the Catholic Church than it does with actual historical evidence.

Within our “modern” (Calvinist) framework, there are only two possible conclusions about the influence of occult practices on the founding of the Mormon church. The first would be to dismiss all evidence as fabricated, narrating all the historical documentation as forgeries and mere attempts to de-legitimize the Mormon Church. The other would be to accept all the evidence, and then conclude that Joseph Smith and the rest of them were all frauds or deluded.

Within the magical worldview that both historians of magic and that the LDS church itself proposes, however, a much more dazzling possibility arises: what if Joseph Smith actually did contact an entity through these Solomonic means?

Here, perhaps my Christian readers are bristling a bit, because within monotheistic frameworks such a possibility must therefore lead to one of two conclusions. Either the spirit called Moroni was truly sent by God and thus the Mormon faith is the true faith, or Moroni was a demon whom Smith mistook as an angel.

From a polytheist framework, however, neither of these conclusions are necessary. (Note to self: strange how this computer just froze…). Instead, it’s completely likely that Joseph Smith did indeed succeed in contacting a spirit through the prescribed Solomonic rituals, and that spirit then had some influence in channeling the texts which later became the Book of Mormon.

This is, by the way, seems to have been the conclusion arrived at by another occultist who claimed angelic contact and channeled a book, Aleister Crowley. Crowley wrote glowingly of Joseph Smith, including him in a list of “men of the highest genius,” and described him positively in his novel, Moonchild.

Crowley isn’t the only occultist to have claimed similar angelic contact, though, and he and Smith had a much more influential and enigmatic predecessor in John Dee. Like Joseph Smith, John Dee used Solomonic scrying methods to contact angels and learn to translate their speech, and even more so than Smith and Crowley, the information he gathered from them had rather far-reaching consequences for our modern geopolitical arrangement. It was from the knowledge he gained through his purported angelic contact that Dee advised Queen Elizabeth to expand the British Empire through colonization, a policy without which Joseph Smith might never have “found” the Book of Mormon.

Of course, ritual magic is not the only means by which mystics and political figures alike have come to experience contact with otherworldly guides which shape the course of history. Joan of Arc, for example, was instructed and guided by figures naming themselves as saints. Whether one believes these accounts or not, it is quite difficult to explain how a peasant girl with no education encountered so many military successes and changed the geopolitical situation of France. At the very least, she — and those around her — certainly believed she was being guided.

Angelic contact and magical practices are also a core mechanism in the founding narratives of all three monotheisms. The Christian story starts with an angel announcing to a virgin that she is with child, and magicians from Persia — guided by their astrological knowledge — arrive to give gifts to that child. It’s through an angel that the prophet Mohammad channels the Koran, and the stone of Mecca was previous to Islam a site of ritual magic for Arabic animism. And let us not forget how often angels “of the Lord” appear to Hebrew patriarchs to guide them towards their “promised land,” while those same patriarchs work miracles indistinguishable from the magical rituals of Canaan and Egypt.

So, then, what if we accept the general premise that spirits — often identified as “angels,” — intervene, guide, and shape the historical trajectories of societies? For a Christian, the next step is about discerning which of the spirits are actually angels sent by God and which are demons. For a polytheist or an animist, for whom the dividing line between the demonic and angelic is merely a matter of perspective, the more interesting question is what these spirits are up to, and why.

And that’s why I’ve been thinking about Orson Scott Card’s book. While there is no spiritual agency implied in the interference of the Pastwatch organization on history, those influenced by them certainly experience it that way. I’m not in anyway proposing a similar time-traveling mechanism occurring in these purported angelic contacts. However, if we think of the limited perspective the researchers had on the trajectory of history, and especially how they originally made things just as bad by guiding Columbus differently, then we have a framework for “angelic” figures would also equally muck things up.

Maybe there are indeed spirits guiding civilizations, inspiring technological advance, intervening in wars. And maybe they’re not always to be listened to. In fact, maybe some of them are eager to drive us into oblivion, to accelerate capitalism to our demise. And here it’s worth remembering that Nick Land, the founder of accelerationism, was involved — along with other figures such as Mark Fisher — in demonological experiments as part of the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit.

I wrote quite a long time ago now that what is needed is an ecology of spirits. By this, I think I also meant a “morality” of spirits, a framework by which those of us giving attention to such things can discern which ones are actually helpful and which ones are destroying us. Older Christianity — Orthodox and Catholic traditions both — had such a thing, and I begin to wonder what was really unleashed upon the world when the Calvinists set about smashing “idols.”

Not that I think the old framework was actually correct, but more that some sort of unbalanced truce had come about between the human world and the spirits. That truce likely needed to end, but no new agreement has ever been reached. We now just pretend that magic and spirits don’t exist at all, and then shake our heads, bewildered, at how the whole world’s gone awry.

Leave a comment